Benthic Ecology Blog Post by Tyler Hee

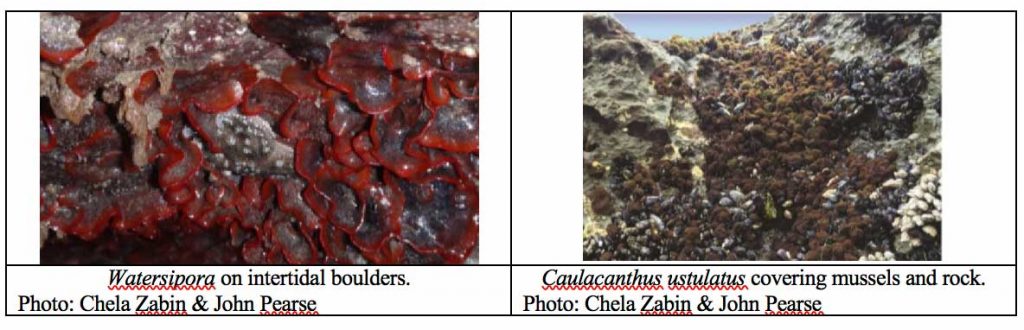

Researchers have found surprising abundances of non-native species in several intertidal habitats (the area of shore exposed at low-tide and submerged at high-tide) and subtidal habitats (the shallow are just below the intertidal) along the important, exposed coastline of Central California. Watersipora a non-native group of bryozoans, or marine invertebrates that live in colonies, and are usually found in calmer waters but was found extensively distributed during the surveys. Additionally, Caulacanthus ustulatu, a species of red turf alga that can form dense patches and outcompete native algae species was found at several survey sites.

Generally, more invasive or non-native species of marine organisms are reported in harbors, bays, and estuaries than in wave-battered, open-coast habitats like those found along Central California. Perhaps due to this difference, there is less concern and more infrequent management efforts for non-natives along the coast of Central California. This indifference however, should be addressed as the subject area of this study is extremely important both ecologically and economicall.

What’s so special about coastal Central California?

The area studied by Zabin et al. covered 275 km, stretching from Pt. Reyes located north of San Francisco Bay southward to Ventura Rocks just south of Monterey Bay. These waters include the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary (GFNMS) and the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS). From estuarine wetlands to rocky shores to kelp forests and open ocean, these two sanctuaries protect important aquatic habitats. These habitats are important for a wide range of fish and marine mammals – some of which are endangered or threatened – that call the waters off Central California home.

These coastal waters, rich with life, are important not only for the animals and other organisms that live there but for the human communities in the area. GFNMS supports 508 commercial and recreational fishing jobs each year with a combined fisheries worth of $53.2 million. Even more staggering, the non-consumptive uses of GFNMS, namely tourism and related activities, supports 1,131 jobs and generates an output of $145.8 million. Not to be outdone, commercial and recreation fisheries in MBNMS annually supports 1,755 jobs and creates an output of $194.8 million. The non-consumptive uses of MBNMS support 542 jobs and generates and output of $69.4 million each year.

Clearly, the areas examined by Zabin et al. are both diverse, ecologically important marine habitats as well as extremely important natural resources that support vital coastal economies for California. Thus, understanding possible trends and developments of potential invasions by non- native species is crucial to the long-term ecological and economic health of the region.

Non-native species found in unexpected areas

The team of scientists surveyed 20 areas in the 275 km stretch of coast from 2014-2015. They looked at an array of intertidal and subtidal sites and recorded the number of and percent of sea floor coverage by non-native species at the study sites. Upon completion of their study, the team found that while numbers of non-native species in these exposed coastal systems are not as abundant across the entire range as in sheltered areas such as harbors, there were some species that were much more common than expected.

The small colonial group of animals, Watersipora, was found in 45% of the study area at one site and 26% lower in the tidal area at the same site. Additionally, the red turf alga Caulacanthus ustulatus, which may compete with native turf alga, was found to cover nearly 20% of the shoreline at one study site.

Despite limited findings, big implications about potential vulnerability in Central California

This study marks the first recorded account of Watersipora in the cooler, wave-exposed waters of Central California. The spread of these invertebrates into waters thought to be too cool and exposed to wave shock could be an important indicator of broader environmental changes to these ecosystems such as warming ocean conditions or adaptation by the non-native animal.

The data collected on the red turf alga, Caulacanthus ustulatus, is the first numerical report for the non-native seaweed. The high coverage at one of the teams Central California study sites is of interest because of the observed impacts this non-native alga has had on native algae and invertebrates in Southern California waters.

The observation of these non-native species in the coastal habitats of Central California merits further attention. There is currently insufficient data to fully understand what trends may or may not be occurring to allow these non-native species to spread to areas previously believed to be highly resistant to such expansion. There is also no information on what impact or damage may be occurring as these species being to occur in new habitats. Further study is needed to ensure effective management decisions of this ecologically and economically important area.

What’s next?

The novel observation of Watersipora and Caulacanthus ustulatus in the typically cooler, open- coast systems of Central California at unexpected abundances may result from by the species or may signal broader regime shifts. Similar to the supposed northward range expansion of tuna crabs off Southern California, the observation of these non-native species in new territory may be linked to changing ocean conditions, namely warmer water. The causes behind these occurrences should be examined because they may help to further explain the changing ecosystem structures of other Central and Northern California habitats like the spike in purple urchins and loss of kelp beds. Thus, before conservation and management decisions can be made in response to changing conditions, we must first ask “what’s driving these changes?” To make decisions before that question is answered puts the ecosystem health and economic value of the Central California coast area in unnecessary jeopardy.

References

Laura Smith-Spark. Red Tuna Crabs Wash Up on San Diego Beaches. 17 June 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2015/06/17/us/california–san-diego-crab-invasion/index.html.

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. Gulf of Farallones National Marine Sanctuary: Commercial Fisheries – Economic Summary. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. 2014. Economic Contributions from Recreational Fishing in Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, 2010 – 2012. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary: Commercial Fisheries – Executive Summary. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. 2014. Economic Contributions from Recreational Fishing in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, 2010 – 2012. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. Dec 2015. Socioeconomics of California’s Northern Central Coast Region: Economic contributions from non-consumptive use. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

Swierts, T., & Vermeij, M. J. (2016). Competitive interactions between corals and turf algae depend on coral colony form. PeerJ, 4, e1984.

Zabin, C. J., Marraffini, M., Lonhart, S. I., McCann, L., Ceballos, L., King, C., … & Ruiz, G. M. (2018). Non-native species colonization of highly diverse, wave swept outer coast habitats in Central California. Marine Biology, 165(2), 31.